I tried to play Blades of Fire like a game I already knew, and I suffered for it. I died, over and over again in MercurySteam’s new action-adventure, the same studio behind Metroid Dread and Castlevania: Lords of Shadow, and it wasn’t until I began to get on board with just how pig-headedly and stubbornly different Blades of Fire is that I realised how exciting it can be.

Blades of Fire was only announced last week, so you’ll be forgiven for not knowing what it is. But it’s coming out very soon, on 22nd May. Somehow MercurySteam kept this game a secret through four years of development. Quite how it managed that with a team of 200 people, I don’t know – it’s a minor miracle. What it means for the game I play at a preview event is that it feels all-but finished, so it makes an incredibly glossy first impression.

We’re squarely in fantasy territory here – rich, overabundant, lavish fantasy, as well as occasionally brutal and twisted. Magic courses through a land teeming with flowers and buzzing with wildlife, and creatures like trolls and elementals romp around. Soldiers who look a bit like the Locust enemies from Gears of War – they have that same chunkiness and sallowness to them – loiter, waiting. In fact, the whole game has a chunkiness to it, a bit like Blizzard games do. Hands and arms are oversized, and buildings and walls are double-thick, which combines not only to make a pleasing visual picture, but to give the game a sturdy feeling, and heft. Remember how chainsawing Locust in two in Gears of War felt? That kind of splattery satisfaction is here too, popping heads like watermelons with huge hammers, or lopping off limbs with scything strikes of your swords.

To give you the topline: Blades of Fire – not to be confused with ice skating film Blades of Glory – is an action-adventure that’s heavy on the combat and features a unique forge mechanic, around which everything revolves. You play as a gruff character called Aran who wakes up one day in a hole of some kind, and crawls out to find himself fighting soldiers and being handed a magical forge hammer that he seems to know and fear. Upon using it, he’s whisked away to a magical forge realm where he’ll return time and time again to make his weaponry.

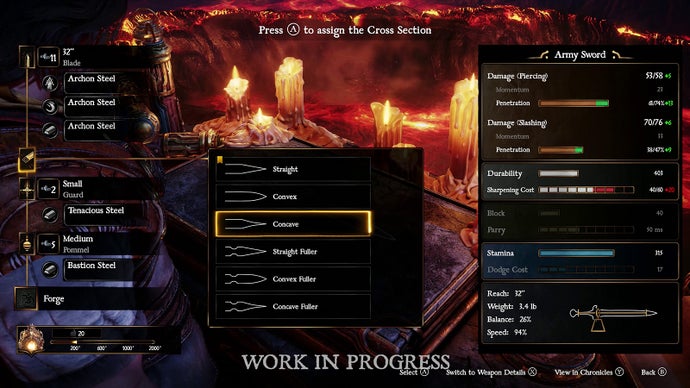

This forge mechanic is not a frivolous thing – I’ve never actually seen anything quite so detailed. It blows out the process of making weaponry into multiple steps and many decisions, all of which alter the properties your weapon will ultimately have. You can choose the metals you use for various parts of the build, for example, and deliberate over blade shapes and cross-guard shapes and pommel types. For hammers, you can consider wood choice for handles. Do you want something huge and heavy, or something small and nimble? Do you want something with good block and parry potential, or something more glass-cannony? There’s a lot to decide upon.

First, you choose the weapon you want to make from a list of scrolls you’ve collected, then you chalk out a design based on the decisions mentioned above. Then you grab a lump of red hot metal and hammer it into shape in a mini-game. What you’re trying to do is bang a pattern into a specific shape, but like the pattern of a graphic equaliser, each time you bang down one end, another end spikes up, so it’s a tricky thing in practice to do. And you only have a limited number of hammer strokes within which to achieve it. At the end, you’ll get a star score for your work. It’s a surprisingly involved process, and an engaging one.

Once teleported back to the game world, you’ll start to understand the importance of the weapons you make. Enemies you fight have vulnerabilities which you discover by locking onto them. Should they highlight in green, your current set-up is good and you’ll do maximum damage against them. But if they (or parts of them) are highlighted in orange, then that’s the signal your set-up could use some improvement, as their armour will soak up some of the damage from your blows. Lastly, if they appear red, you’ve got a problem, and your weapon attacks will do no damage at all. It’s a traffic light approach, in other words: you highlight an enemy and cycle between weapons and fighting styles until you find one that’s green to go.

I’m used to this idea – that different weapons work against different things – but I’m not used to a game negating attacks entirely if they’re mismatched. I’m also not used to this particular way of switching between them. Here, changing weapons involves holding down the right trigger and pressing the right stick, but changing fighting styles requires only a tap of the right trigger (or at least it did on the PS5 controller I was using that was connected to a PC). Fighting styles, incidentally, alternate the way you use a sword, preferring either the tip for thrusting, or the sides of the sword for slashing. Hammers, meanwhile, only crush, as far as I can tell. None of this sounds complicated, I know, but in the heat of battle, it’s fiddly, especially when different enemies within a group require a different approach.

Blades of Fire’s combat system is also awkward to begin with. I mean, who puts a dodge-roll on the left bumper, for goodness sake? It’s typical of the way in which this game does things its own way and no one else’s. The face button attacks are different, too. Rather than denoting light or heavy attacks, here they determine the direction of your attacks. Different face buttons correspond to a strike from the left or right, or an attack to the head or body, and if you hold the button down, a mutilation – which is what you think it is: a potentially fatal and very gory power attack. Remember the watermelon head-pops I mentioned? Hold down triangle to achieve them.

It’s an unusual system, but Blades of Fire does it this way to tie into the traffic-light system outlined above. Enemies can have independent areas of vulnerability on them – patches of green, if you like – so if they’re vulnerable on their torso, you want to aim for the body, and if they don’t have a helmet on, you should pop their head. It’s a lot to take in all at once.

Exacerbating the awkwardness is the game’s difficulty. To me, Blades of Fire sits somewhere between a Soulslike and the modern God of War games. Actually, there are quite a lot of parallels to God of War in how you’re a gruff old fella adventuring with a bright young lad called Adso; you suddenly take it upon yourself to kill an evil queen, and Adso pledges their service to you, offering useful sidekick help by highlighting enemy weaknesses and assisting in solving puzzles for you. The game has the impact of God of War in combat, too, but it punishes you more like a Soulslike would, not by robbing you of experience, but by making you drop your handmade weaponry when you die. You’ll retain a default sword, but if you want your stuff back, you’ll have to fight your way through respawned enemies to get it – which can be tricky when you no longer have some of the specialised weaponry you’d want to use against them.

Back to the forge you go, then, and it’s on my fourth or fifth visit there in the 90 minutes I play that the forging starts to chafe a little. You can, thankfully, instantly remake weapons you’ve made before, to save time, but the process as a whole began to lose its appeal somewhat. I felt as though I was enduring rather than enjoying what I played.

But then it all started to change. It started with slowing down and nosing through the game’s menus and built-in tips to see what I was doing wrong, and there, I learned the nuances I’d been missing. Armed with that new knowledge and sharper weapons, and a stamina regen trick (hold down block – unusual), I re-entered the world and suddenly found myself achieving, trouncing a huge troll that had been harassing me for the last half-an-hour. A troll that personified the game’s attitude towards me, I think – a stubborn obstacle to be overcome. My abrupt reorientation complete, I was finally able to truly begin.

Despite how it might sound, I really liked what I played of Blades of Fire. I have huge admiration for teams that stick to their own design principles despite what other games are doing, and that’s what it feels like here. Blades of Fire is different. It has ties to a game made years ago by some of the MercurySteam founders, called Severance: Blades of Darkness, but only loose ones. Mostly, Blades of Fire is new, and it feels it. And because MercurySteam is co-funding it, it gives the studio a chance to finally have something of its own, having spent years winning acclaim for other company’s brands.

“For an independent developer, the industry ocean is tough to navigate,” CEO Enric Álvarez tells me. “We think that if we are flying with our own wings it will give us more chances. It will give us autonomy. It will give us full responsibility; we’re taking part of the risk. But for us, more than a risk is an opportunity to create something that belongs to us and that we don’t rely on anyone to make it happen. In that sense, Blades of Fire is an opportunity for us, from a business and also from a creative standpoint. It involves some risk, yes. What in life doesn’t involve a risk?”

Whether it will come together as a cohesive whole, I couldn’t possibly say yet, but the glimpse I’ve had is exciting. Roll on, May.

This coverage is based on a press event, for which food and travel was paid by 505 Games.