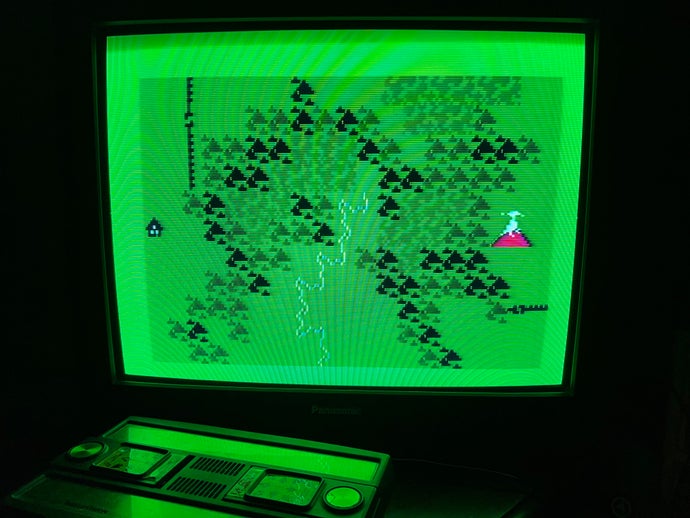

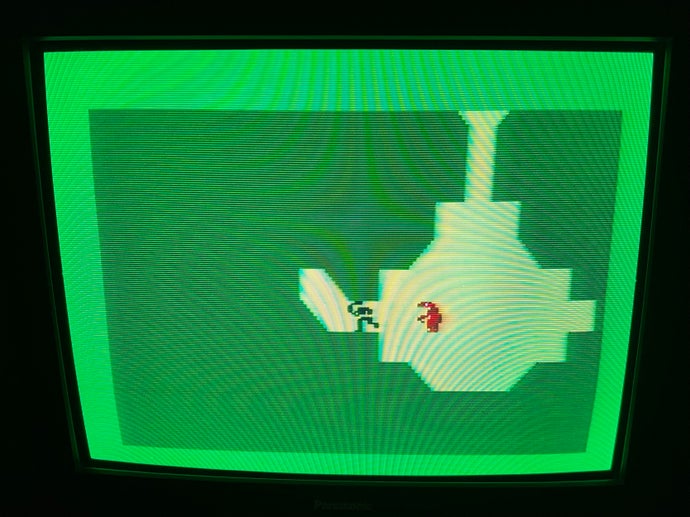

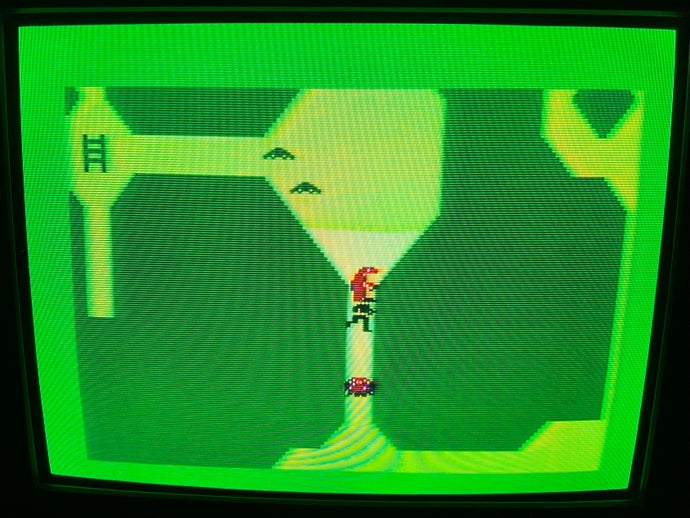

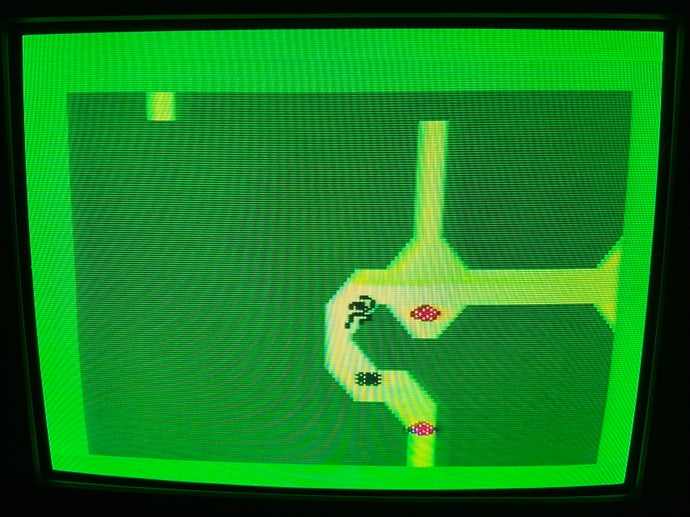

An ancient quest, one the bards will sing of in every tavern this side of Cloudy Mountain. A heroic ranger, travelling mountain passes, fjording rivers and hacking her way through cursed forests, protected only by her wiles and the taught string of her trusty bow. Her arrows, enchanted by the witch queen, bounce off cavern walls, apt at slaying all manner of rat, bat, snake, and conniving spider. She tracks them through the mazes encountered on her journey, using scat and skull alike to stave off their advance – and that of the tunnels’ vicious demons and dragons whose attacks land close enough to shave the very fibres of her cloak, but just can’t seem to bring her down.

And so she hunts, careful to avoid the shambling pink blobs that are said to be indestructible even to the magic weapons of the brave adventurers who set out for Cloudy Mountain, never to return. By hook and crook and skin of teeth, she rides there and confronts the legendary winged dragons that guard the two lost halves of the Crown of Kings. The crown shards sport the midnight sigil of the ancients. Three arrows notched and flown straight through the creatures’ hearts are the only way to take them down. The ranger recovers one shard, then the other. A fuzzy, computerised blast of sound greets her in her triumph. You return to the map screen, relinquishing control. You’ve done something I’ve never done. You’ve beaten Advanced Dungeons & Dragons on the Intellivision.

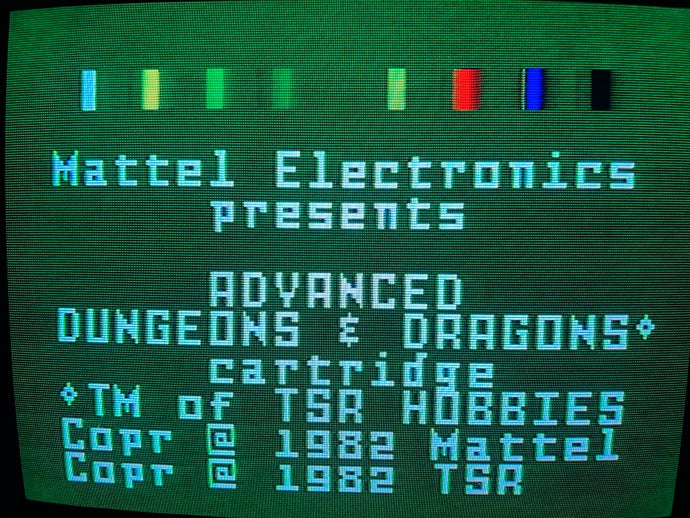

It was once the most technologically advanced piece of Dungeons & Dragons media known to humankind. Its mountain mazes, made up entirely of green and yellow pixels, held wonders and horrors for those with courage enough to brave their depths. Its enemies scaled in difficulty, from one-shot KO rats, to two-shot minibosses, all the way up to the winged dragons in the fabled Cloudy Mountain that took three arrows to vanquish. The game’s sound design was enthralling, the back of the box quick to assure players – and rightfully so – that “exciting sound effects highlight game play.” You were alerted to the presence of nearby monsters in the maze by the sound of their wings or the slithering of their bodies through the mud before seeing them at all. To find them, you had to uncover the rest of a tunnel by walking through it, and by that point it could be too late.

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons starts you out with only three lives and three arrows. Many enemies are faster than your character, and if they touch you, you lose a life. Once you run out of arrows, which you aim by pressing a number on the Intellivision’s control pad, you have to find more in the tunnels, or you’re a sitting duck. It feels a lot more like a prototype survival-horror game than any RPG-esque D&D experience we’d recognize today. That said, it showcased the Intellivision’s greatest strength as a console that enraptured an entire generation of early at-home gamers: its ability to activate players’ imaginations in spite of technological limitations.

My grandparents bought my dad his first Intellivision after a rare visit to New York City in 1981. He was a high school sophomore. A misfit at his Norfolk, Virginia private school who loved old Marx Brothers movies and computers. They all wandered into a department store, and once he found the little room dedicated to Mattel’s latest electronic wonder, complete with technicolor advertisements and spotlights trained on the machine in all its futuristic glory, that was pretty much that. Soon, he brought one home. His fascination with the odd wood-panelled box – that by today’s standards looks more like an ancient telephone than a gaming device – grew with each cartridge he snapped into the Intellivision’s card reader. He liked sports games the best, especially hockey, which amounted to opposing coloured blobs paddling the pixelated puck from side to side amidst crashes of strange sounds. But he also remembers the disorienting mazes of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, which was released in 1982, two years after the Intellivision launched, and in the midst of its corresponding tabletop role-playing game’s first steps into the world of mainstream entertainment.

The original Dungeons & Dragons was a small box set of three booklets published in 1974 and written by the father of D&D, Gary Gygax, and his collaborator at the time, Dave Arneson. It was published by Tactical Studies Rules, Inc. (TSR) as what was essentially a supplemental playstyle for players already familiar with wargaming. Despite its humble origins, the game outgrew its original target audience, gaining a cult following among a younger crowd made up primarily of high school and college-aged boys. Later in the 70s, in an attempt to be more inclusive to casual players while spurring the growth of the game’s crunchier mechanics, TSR published two distinct rulesets: Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set and Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. This split would persist up until Wizards of the Coast bought the foundering franchise in 1997 and released D&D 3rd Edition three years later, unifying the disparate rulesets after their two decades apart.

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons for the Intellivision hit the scene right as D&D mania began to sweep the United States in the eighties. Worried mothers would stay up late talking in hushed tones about how they were afraid their sons were engaged in demon worship, having glimpsed pentagrams and strangely shaped-dice littering their desks, ruining the domestic order of their ceramic-topped kitchen counters. Young creatives became fascinated with the worlds of high adventure contained within their heads, and that fascination proved to grow alongside them into the modern day.

After a major surgery in college, my uncle gave me an Intellivision as a gift. Of the cartridges he included in my care package, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons became an instant favourite. It helped me connect with my dad and rekindled my interest in video games old and new. And it ultimately led me to playing Baldur’s Gate 3, which I’ve now completed almost twice in nearly 150 hours of play. I’ve been both a DM and a player for many a late evening session of the tabletop game that inspired both, and though BG3’s mechanics – of course – hew much closer to the modern tabletop ruleset, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons better captures the spirit of the franchise’s meteoric rise. The ethos of the game that’s inspired so many of us to let our nerd flags fly, to romance Astarion and learn about those mysterious tattoos, even to spend hours writing a fantastical story – complete with monster stat blocks and skill checks – that only a few friends will ever know exists.

Because D&D started out as a do-it-yourself dream. A low-fidelity concept given over to the human mind as fuel for hungry imaginations. A perilous adventure in a box. And, as I sit next to my girlfriend and dad, trying for the hundredth time to get to Cloudy Mountain, questing past demons and dragons only to misfire an arrow and meet my bloopy demise, I can’t think of anything that will ever make me feel closer to the intertwined histories of gaming that help make me who I am today.

Now, of course, Dungeons & Dragons has experienced a resurgence unlike any other modern media franchise. After an era of relative disinterest between the later nineties and pre-2010s, it’s since spawned everything from actual-play podcasts to feature films. A revised 5th edition tabletop ruleset is coming this fall, while last year was dominated by Larian’s smash hit RPG, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons’ most curious video game grandchild. I use the word curious here because, on the surface, nothing connects BG3 and its ancestor beyond bows and arrows, rats, and the D&D name.

In fact, remove the name and you have two distinct experiences that bear no relation to one another. One’s the best role playing game ever made, with branching storylines, steamy romances, and turn-based battles in free space complete with a nuanced physics system. The pinnacle of customizability, immersion, and graphical nuance. The other’s a blip-blooping clunk through samey environments, whose difficulty is as much due to its technological limitations as its designers’ intent. But play both, and you’ll come out feeling immersed in the same form of grand adventure: one uniquely of your own making.