Silent-era American films have a better survival rate than classic video games. Let that sink in. The findings of 2023’s Video Game History Foundation report suggested that 87 percent of classic video games released in the United States are “critically endangered”. What this means materially is that only 13 percent of games released before 2010 are readily accessible today. Historically, preservation has been a concern exclusively for academics and dedicated game history buffs, but in the last few years, preservation as a field has made significant progress in puncturing the games culture bubble. As stories of live-service games being taken offline before they have a chance to find an audience become more frequent, the awareness that our favourite digital pastime is under an existential threat is more apparent than ever.

While physical and technological obsolescence is a given where cartridges and discs will decay and be lost to time, tears in the rain and all that, we are now in an economic and cultural landscape where one could accuse larger studios of not recognising their own contribution to that 87 percent statistic – especially if we think a little too hard about what happened with last year’s Concord, which lasted just two weeks before Sony took it offline due to poor sales.

The reality is that games are more complicated artefacts than ever, which introduces all sorts of complexities to the preservation methods developed over decades of academic and community work. Video games are slippery, they’re ephemeral, they don’t exist in one place or in one discrete form. They live in our memories more than they do in physical media. As the stuff – code, assets, save data – that makes up games continues to disappear into black-box server rooms, preservationists may need to start thinking about video games more as a shared artistic practice like dance or language than material artefacts.

“I think the game industry has always found itself in an uphill battle to prove that video games are art, and especially internally here we often think that that’s kind of a settled question at this point that, of course, video games are art,” says Phil Salvador, library director at the Video Game History Foundation. “But there is still a barrier towards at certain levels, people perceiving games as being commercial objects versus being art that needs to be preserved.”

Salvador was instrumental in the launch of the Video Game History Foundation’s new digital library. Last year, he worked on the recent campaign seeking a DMCA exemption from the US Copyright Office that would allow libraries and archives to remotely share games in their collections. Unfortunately, this exemption was denied last year, with opposing arguments from the Entertainment Software Association that argued the DMCA exemption would harm rights-holders as well as the classic game market.

While games culture has opened its eyes to the value of preserving games history, this is far from universal; especially at the intersections where video games have become massively commercial entities with attached movie franchises, licensing deals and lucrative microtransaction models. But that doesn’t mean that the Video Game History Foundation is giving up. “In talking with individual developers and publishers and people who work for game companies, they understand what we’re doing, but it’s difficult for that message to filter up through the game industry to an executive level.”

While games preservation has been largely a product of passionate hobbyists, the call to professionalise the field is gaining traction as organisations such as the Embracer Group Archive and the Video Game Heritage Society fill the gap between the hobbyists and the game industry. Working with rights-holders is preservationists’ direct line to the tools and resources necessary to build sustainable models that can protect games history.

“I think on the preservation front, it’s vital that we have these connections with bigger companies and developers,” says Isaac Murphy, digital producer at Lost in Cult, now a household name for publishing lovingly crafted collections of games criticism and documentary books.

Reflecting on how game rights-holders interact with the Lost In Cult model, Murphy says: “It means we can use their intellectual property in our books. We make a lot of official books now, whereas before with [our] Lock-on [series of gaming journals], we’d have to get as close as we can without breaching IP.”

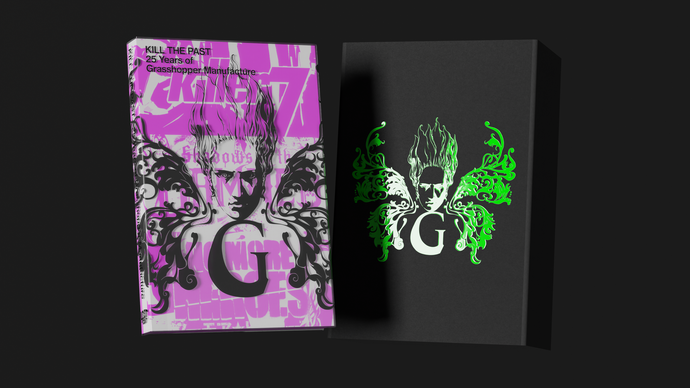

Lost in Cult recently announced a 25-year retrospective documentary book chronicling the history of cult Japanese studio, Grasshopper Manufacture. This book stands as material evidence of the collaboration between preservationists of culture and producers of commercial video games. “Grasshopper was very accommodating of what they shared, they essentially sent over a folder and went, ‘There’s loads of stuff in there just like having a rummage around’,” Murphy told us. “There were things like pitch decks for some of their games, lots of concept art, and documents that are sort of business-sided and fairly dull, but to an archivist or to an enthusiast or a preservationist, it’s incredible to see because they are just sitting on this world of history and it’s just on a Google Drive.”

However, not every preservation project leads to the promised Google Drive full of unearthed treasures. The recent shutdown of Nier Reincarnation, the mobile exclusive sequel to Square Enix‘s pair of existential action RPGs, birthed Accord’s Library. This was a collective of Nier fans attempting preserve the three-year, evolving story without access to the servers that hold all the assets. Accord’s Library has now closed following contact from Square Enix’s legal team.

“I think that’s one of the challenges is that a lot of this only happens when there’s an internal advocate in the right place at the right time,” says Salvador speaking on the collaborations with game developers. “[The Video Game History Foundation] heard from someone at a large company that they were effectively in charge of what I would describe as a giant room full of old material that they didn’t know what to do with. If that person is laid off, who knows who’s in charge of that now or what even happens there anymore.”

Salvador hits on a perhaps underrepresented threat produced by the current precarity of the video games jobs market. With game studios churning through staff members, in-house preservation advocates are going to become increasingly rare. “These kinds of questions require navigating hierarchies of companies and figuring out what these conversations are and who is in a place to advocate. It’s something there hasn’t really been a lot of dedicated organisational support to doing.”

Without that support, what are game history fans meant to do? Well, if we turn to historical precedent, what they tend to do is steal. The majority of preservation projects have been ad-hoc, community-led deep dives into specific niches requiring less-than-legal DRM workarounds. While these projects can be collections of sprites from fighting games, some of these hobbyists revive MMOs wholesale with functional servers and support staff, such as Warhammer Online: Return to Reckoning. The potential and ingenuity of the video game community supersedes the need for permission from rights-holders a lot of the time.

Bypassing legal permission, however, does not compromise the integrity of preservation projects argues James Newman, a professor of media and computing at Bath Spa University in the UK. In 2012, he published Best Before: Videogames, Supersession and Obsolescence, a formative book in the academic field for conceptualising video games preservation methods beyond traditional museum and archival approaches.

“There is a version of [preservation] where we don’t need the rights-holders, and actually fierce independence could be a really important approach as well,” Newman says. “There’s a caution that needs to be exercised in terms of inadvertently mistaking publicity and marketing for preservation and exhibition.”

Professor Newman raises an important complexity in collaborating with rights-holders: at a certain point, cultural institutions run the risk of becoming an extension of their marketing departments. And that, in turn, reintroduces the friction between the cultural institutions that want DMCA exemptions and materials for archival and historical purposes, and the rights-holders who want to maintain a vice-grip over their intellectual property and any future capital gains from it.

That being said, Salvador notes that while an antagonistic approach can be admirable – exemplified by Jason Scott of the Internet Archive’s infamous ‘Steal From Work‘ rhetoric – it can also further obfuscate the value of video games from the powers that be. Reflecting on the DMCA exemption rejection, Salvador says: “Having it framed as a combative battle between the industry and the advocates is one of the things that may make larger institutions like the US government reluctant to move on games preservation.”

“Speed runs, interviews, oral histories, whatever it might be, they’re not the context, they are the thing.”

A new approach is needed, then. If physical game media is soon to be dust and live-service games can be shut off on a whim, then preservation could become more about preserving memory and experience than anything else. “What I would love to see is a documentary approach, and I’m not talking necessarily about a series of 45-minute Netflix specials,” says Newman. “[A documentary approach] begins to conceive of the game as a designed object, an object which is played with and to begin to create that kind of constellation of materials that helps us understand the various different ways in which it was constituted, played with, reimagined and redesigned. The playable artefact might be one of those, but I don’t see it as being at the centre. Speed runs, interviews, oral histories, whatever it might be, they’re not the context, they are the thing.”

What Professor Newman is invoking here is a way of thinking of video games as producers of meaning in themselves. A contemporary preservational method should look to capture what the game meant to people at the time it was played and look to continue to capture what the game means to people today. “You recognise the meaning these games have for different people, in different contexts in different parts of the world, at different times in their life as well. I think that’s one of the liberating things that comes when you stop thinking about trying to secure the code.”

Now, while nostalgia is a common catalyst for interest in games history, it’s also one of the cultural threats to a more liberated means of preserving games. Speaking on Lost in Cult’s editorial direction, Murphy told us, “We want to write less ‘Oh, wasn’t it good back then?’ [articles]. I feel that’s a bit useless. Like, what are we learning from that? Apart from being smug about the past?”

This general smugness is largely attributed to the demographic of folks working in the game history space. A demographic that needs to develop if this preservation is to be taken seriously as a practice. If we want to capture the cultural importance of games, we can’t just rely on the rose-tinted view of games history from one demographic – which, right now, is predominately white men over the age of 35. We need to understand what these games meant for people of all backgrounds. Simply put by Professor Newman: “Nostalgia will be the thing that stops us coming up with approaches and methods that really could be innovative.”

So where does that leave us in 2025? Well, the Video Game History Foundation is going to continue to advocate for the importance of games history to the wider commercial industry, Lost in Cult is looking at expanding into physical games publishing, and academics such as Professor Newman are looking to develop methods of that narrativised approach, to capture the “constellation of materials” that make up the stories of the video games we love, throughout their creation and beyond.

Salvador expressed it best in my conversation with him. We were discussing the recent re-discovery of Piglet’s Big Game that went viral last year. What was considered, even at the time, a movie tie-in 3D adventure game not worth a second glance, has since been re-evaluated as a potently atmospheric survival-horror game for kids. “I’ve been scanning a lot of press kits we have and going back they are framing it as like a spooky game which was totally missed by all the reviewers,” said Salvador. “This game has had a resurgence and a rebirth because of people wanting to play it and understand it and get the context of how and why it was made.

“If I could idealise what the future of game history looks like. I want a thousand Piglet’s Big Game. Who knows what the rights clearance is for Disney and the developers, but it has taken on this new life and appreciation from people kind of doing their own thing with it. That is something that gives me hope.”