Joy is a bit underrated, I reckon, but at Summer Game Fest this year it felt like the closest thing to a running theme. Astro Bot and Lego Horizon Adventures were both a breeze, playful, ebullient family games that put all their focus on simply being a good time. The Plucky Squire, an action game with a domestic dimension hopping twist, however, probably just pipped them to the position of first, in the race to be the most joyful experience I had all week.

In fact, it was one of the most joyful I’ve had in video games for a little while. The Plucky Squire is a delight.

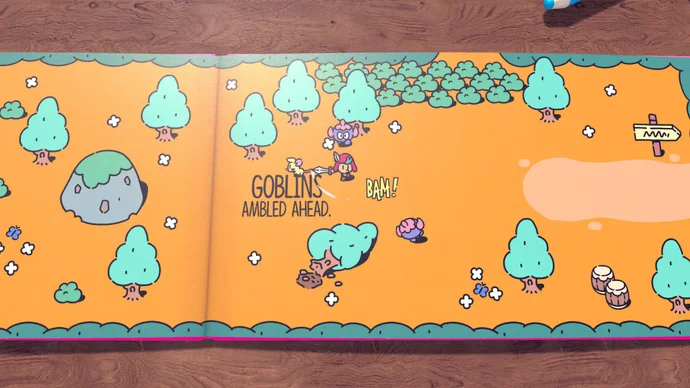

The setup here involved an opening sequence in a 2D part of The Plucky Squire, the main storybook. What’s striking is how the edges of the pages, while always visible, seem to just melt away here. You are in this, playing a top-down Zelda-like adventure, whacking little enemy blobs with your sword or using a nice little throw-and-recall system for it like a manually-summoned boomerang. You hop ledges and chasms from set, green swirls in the ground, which take you to corresponding green swirls on the other side. Then you hit an obstacle – a big spinning mincer that seems rather gnarly and, frankly, suspiciously out of place for this twee little pastel-hued tale – and hop on another swirl and – oh! – you’ve jumped right out of the page.

I will never get tired of moments like this. The world-turning of Fez, the portal-hopping of Portal, the matching lines of Superliminal or Manifold Garden. The Plucky Squire’s is different – it’s not an on-demand thing, but a shift that happens at set locations – but it feels just as magical. Just as instantly transformative, just as effective at leaving me with a massive smile.

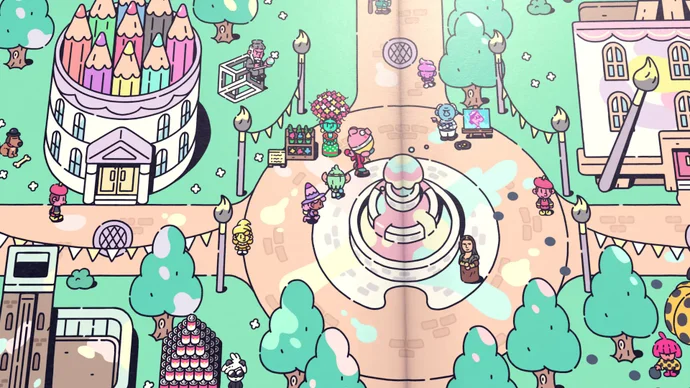

The first of these moments took me out into the 3D desktop world. Suddenly you’re no longer in Zelda but in Toy Story, A Bug’s Life. You’re hopping up onto little piles of notepads and along playing cards or precariously, playfully balanced rulers – the telltale desktop of a procrastinator, I know a comrade when I see one. A little wizard, perched on various objects of stationary around the desktop, offers advice. Enemies taunt you with attacks from ledges you can’t quite reach with your sword, or that sit just too high for a jump. We’re in a 3D platformer of old. I smell an unlockable ability.

I smell correctly: around the world are other characters in need of help, who grant you an ability in return. The most notable is a jetpack, which spurts out a long tail of flame as you climb a little higher – flame that is lit quite wonderfully, I should add, flickering and glowing, and casting shadows across a world that seems to be set some time around twilight.

Unlocking this jetpack required some work. I’d come across another little glowing warp swirl, this time on the surface of a mug. Onto the mug I went, themed after a kind of space cartoon, and a little rocket’s in distress. His parts have been strewn across the desktop and are in need of recovery. (If you’re wondering what the story behind all this 2D-3D crossing of worlds is, by the way, there is a suitably charming magical explanation: the evil wizard, Humgrump, is using his magic to try and control the story of the book you’re from, and that seems to also be turning everything else upside down.)

With those parts collected and jetpack acquired, more questing continues. On a vertical wall, a portal takes me into a retro 2D platformer, with a sketched-out, colouring pencil art style of its own, a doodle on the wall, as I hop ledges and dodge more patrolling enemy spikes and blobs. Another mission has me using my jetpack to find and, with its spouting flame, light several candles hidden around the world. A plastic toy tub provides a moment of genuine magic: a self-contained game of its own.

This is effectively a round of Resogun – Resotub? Does that work? – as the plucky Jott is transformed into a shades-wearing 80s action hero with jetpack and laser gun, and you work your way around the cylindrical tub surviving wave after wave of enemy spaceships and rescuing civilians. Another art style – something like a retro cartoon here? – another mechanic, another moment of impossible charm.

What you realise, playing through The Plucky Squire, is that this must be the inimitable work of an artist – and it is. James Turner, formerly a designer of Pokémon like Golurk, Sinistea and Gigantamax Pikachu at Game Freak, is one of the founders of developer All Possible Futures. Turner explains some little bits of development magic to me – how the 2D minigames and storybook segments were created by actually projecting these 2D elements onto a 3D world, for instance, which I find almost impossible to understand. Suddenly it’s impossible to unsee the artist’s hand on everything – shifting art styles for one, but also shifting perspective, shifting of the frame and the angle. Even the collectibles are a wonderful artistic touch: each one is a poster of a different character in the game, which is in fact the actual concept art for those characters from development.

And what you feel above all, really, is the love an artist has for their creations. The Plucky Squire is joyful and delightful and inventive, but it’s also a game that’s been made with indisputable care. The kind of care that quite literally leaps out of the page.